Table of Contents

- Processes and Threads

- Why Concurrency is Hard?

- Go Routines

- WaitGroups

- Go Routines and Closures

- Go Scheduler

- Channels

- Deep Dive - Channels

- Select Statement (Notes to be added)

- Sync Package

- Race Detector

Notes prepared from below resources:

Concurrency is composition of independent execution computations, which may or may not run in parallel.

Parallelism is ability to execute multiple computations simultaneously.

Concurrency enables Parallelism.

Processes and Threads

- Why there was a need to build concurrency primitives in Go?

- The job of the OS is to give fair chances for all processes access to CPU, memory and other resources.

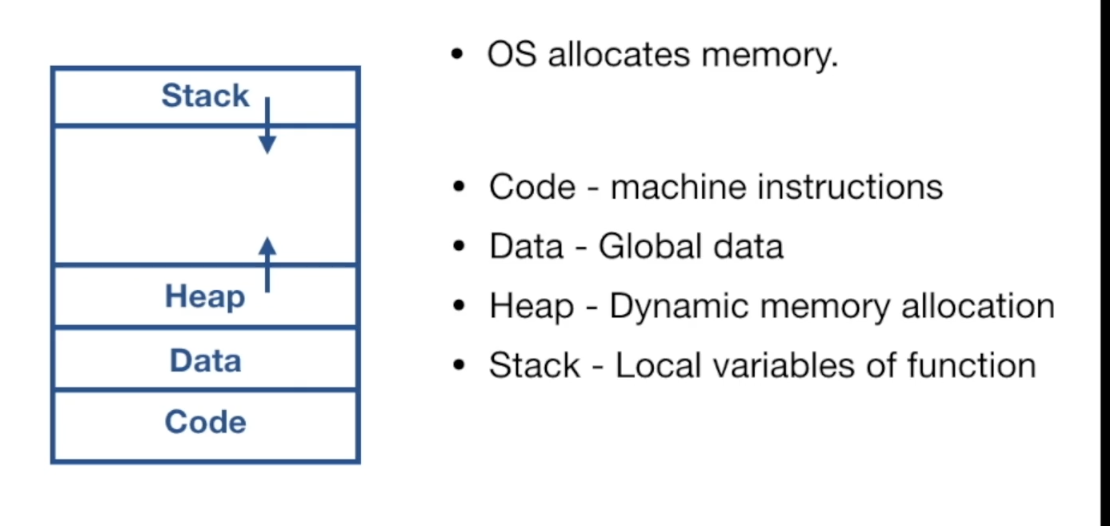

What is a Process?

- An instance of a running program is called a process.

- Process provides environment for program to execute

Threads

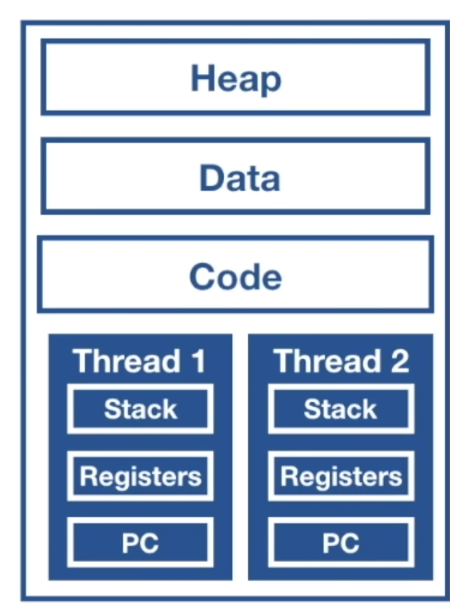

- Threads are smallest unit of execution that CPU accepts.

- Process has at least one thread - main thread.

- Process can have multiple threads.

- Threads share same address space.

- Threads run independent of each other

- OS Scheduler makes scheduling decisions at thread level, not process level.

- Threads can run concurrently or in parallel.

Can we divide our application into Processes and Threads and achieve concurrency?

- Yes, but there are limitations.

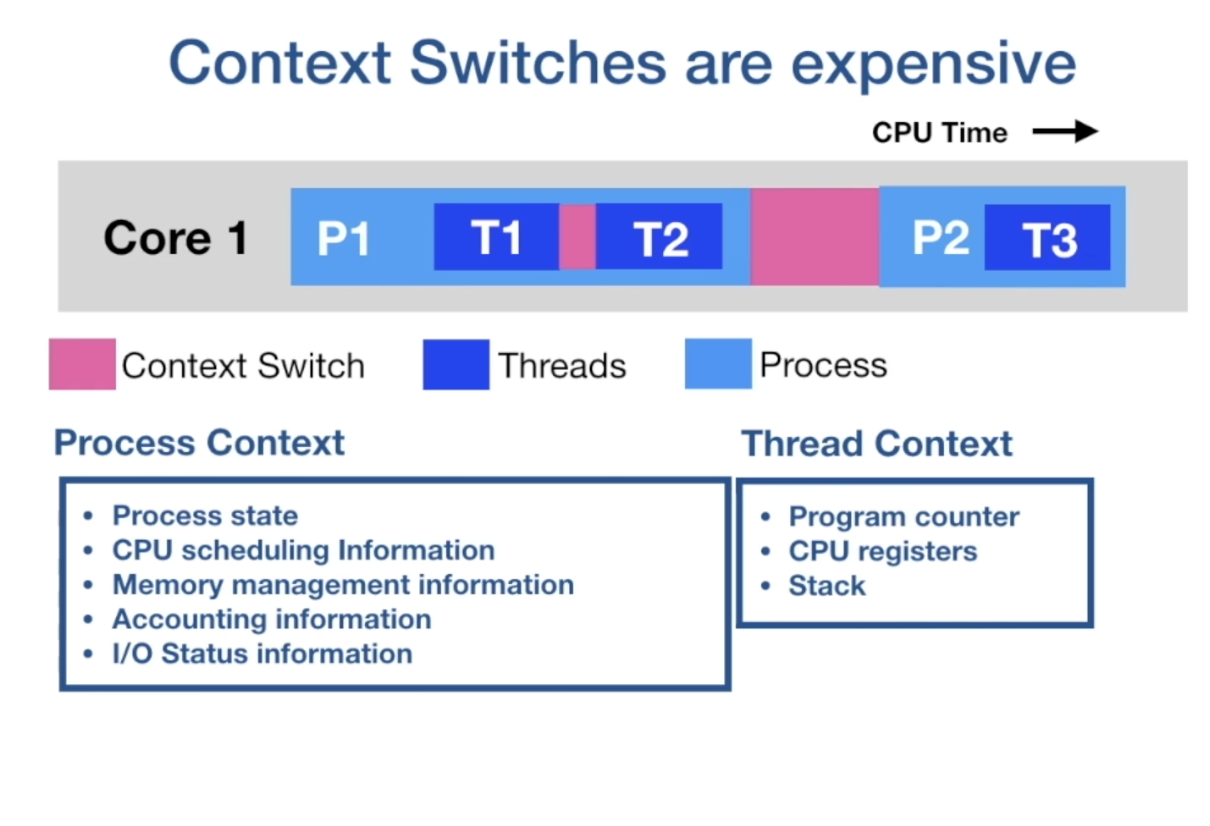

- Context switches are expensive.

- CPU has to spend time on storing the context of current executing thread/process and restoring the context of upcoming thread/process.

- From the above image you can see context switching of threads is less expensive that context switching of processes.

Can we scale number of threads per process?

- Not much, if we scale no. of threads per process then we hit C10k problem.

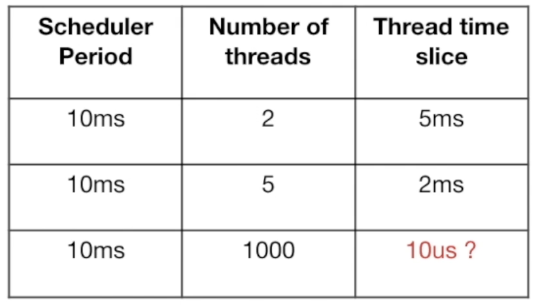

- Scheduler allocates a process a time slice for execution on CPU core.

- This time slice is equally divided among threads.

- From the table we can see that if increase thread count then thread execution time becomes very less and CPU spends more time on context switching than thread execution.

- Another issue is Threads are allocated a fixed stack size.

Why Concurrency is Hard?

- Shared Memory

- Threads communicate between each other by sharing memory.

- Concurrent access to shared memory by two or more threads can lead to Data Race and outcome can be Un-deterministic.

- We need to guard the access to shared memory so that a thread gets exclusive access at a time.

- It’s developer convention to lock() and unlock().

- Locking reduces parallelism. Locks force to execute sequentially

- Inappropriate use of locks can lead to deadlocks.

- Circular wait to lead deadlocks.

Go Routines

Communicating Sequential Processes

- Each process is build for sequential Execution.

- Data is communicated between processes. No shared Memory.

- Scale by adding more of the same.

Concurrency tool set

- Goroutines

- channels

- select

- sync package

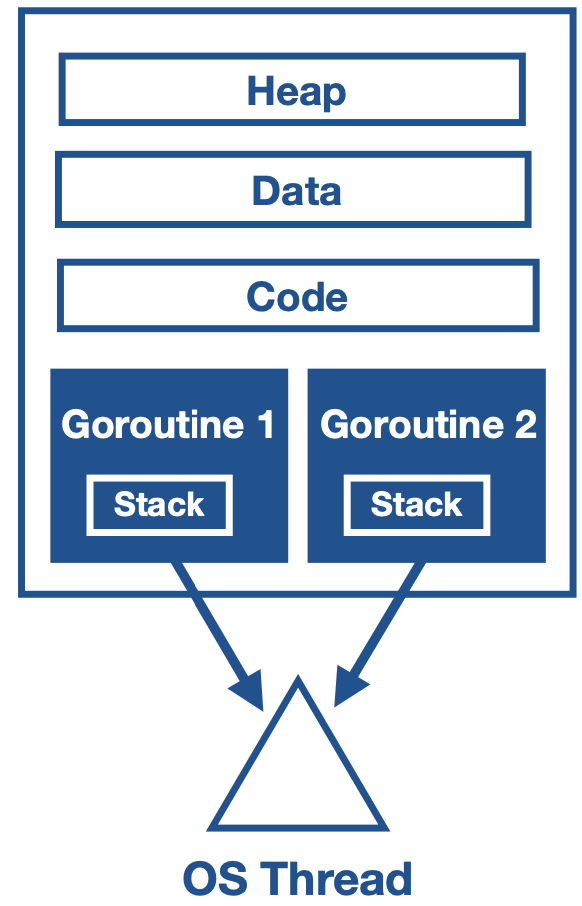

We can think Go routines as user space threads managed by go runtime.

Go runtime is part of the executable, it built in to the executable of the application.

Go routines are extremely light weight. They start with 2KB of stack which grows and shrinks as required.

Low CPU overhead - three instructions per function call.

Can create hundreds of thousands of go routines in the same address space.

Channels are used for communication of data between go-routines. Sharing of memory can be avoided.

Context switching between goroutines is much cheaper than thread context switching as go routines have less context to store.

- Go runtime can be more selective in what is persisted for retrieval, how it is persisted, and when the persisting needs to occur.

- Go runtime creates worker OS threads.

- Go routines runs in the context of OS thread.

- Many go routines execute in the contest of single OS thread.

WaitGroups

- Race Conditions

- Race Condition occur when order of execution is not guaranteed.

- Concurrent programs does not execute in the order they are coded.

sync.Waitgroupis used to Deterministically block main go routine.

Go Routines and Closures

- Go routines execute within the same address space they are created in.

- They can directly modify the variables in the enclosing lexical block.

- Go compiler takes cares of the moving the variable from the stack to heap, to facilitate the access to the go-routines even after the enclosing function is executed.

Go Scheduler

- Go Scheduler is a part of go runtime. It is known as M:N scheduler

- It runs in user space and used OS threads to schedule go routines for execution.

- Go routines runs in the context of OS threads

- Go runtime creates number of worker OS threads, equal to GOMAXPROCS (default value of no. of processors on machine)

- Go scheduler distributes runnable go routines over multiple worker OS threads.

- At any time, N go routines could be scheduled on M OS threads that runs on at most GOMAXPROCS no. of processors.

Asynchronous Preemption

- This prevents Long running Goroutines from hogging into CPU, that could block other Go routines

- The asynchronous preemption is triggered based on a time condition. When a go routines is running for more than 10ms, Go will try to preempt it.

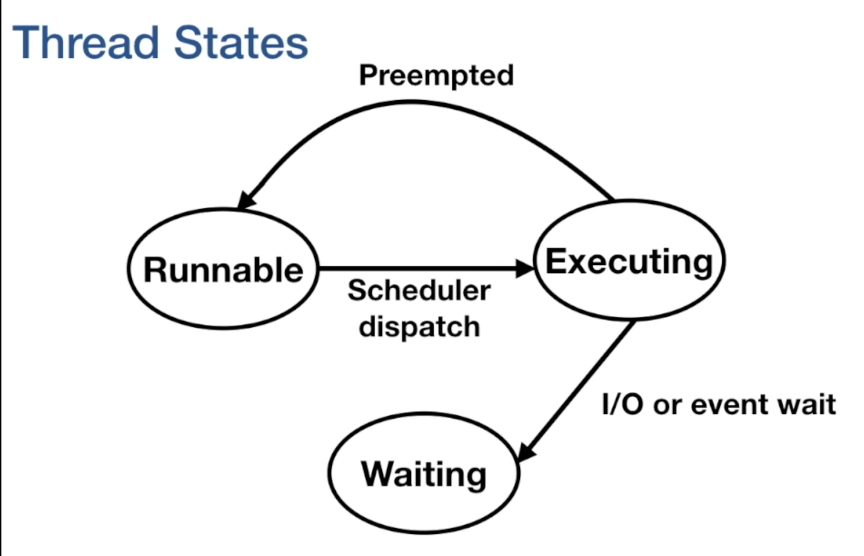

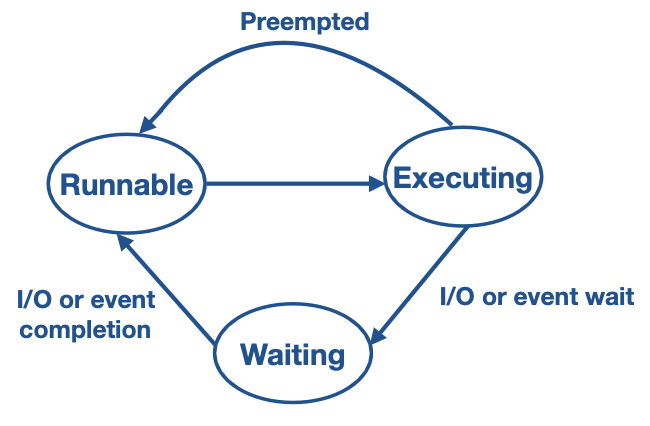

Go Routine states

- Runnable - When it is created, it is in runnable state and waiting in the run queue.

- Executing - It moves to executing state once the go-routine is scheduled on the os thread

- If the go routine has crossed it time slice, then it is preempted and placed back in run queue.

- Waiting - If the goroutine is blocked for any thing (like i.o or event wait or channel), then it is moved to waiting state.

- Once the i/o operation is complete, they are moved back to runnable state.

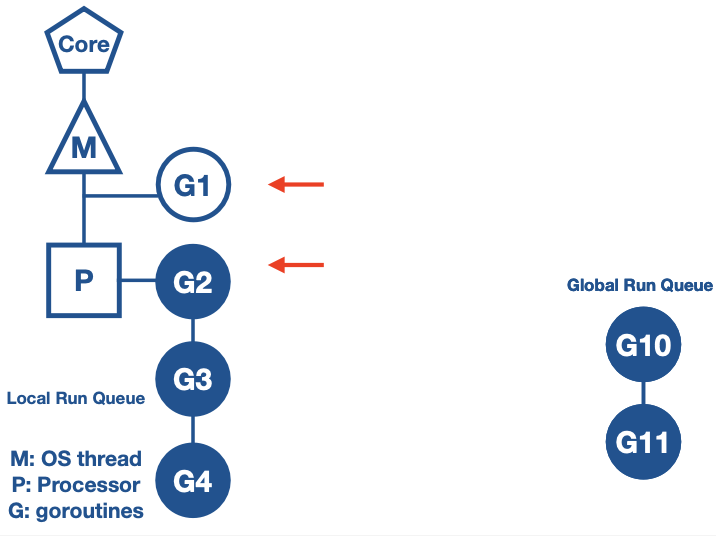

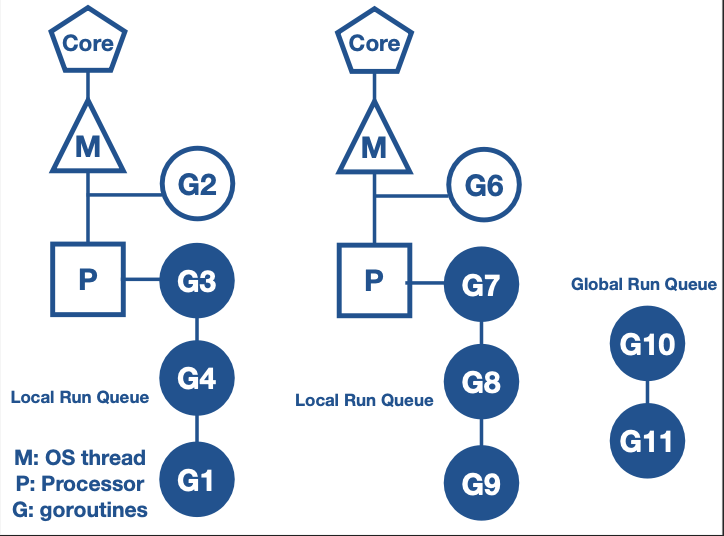

Components of Go-Scheduler:

M - represents OS thread.

P - is the logical processor, which manages scheduling of goroutines.

G - is the goroutine, which also includes scheduling information like stack and instruction pointer.

Local run queue - where runnable goroutines are arranged.

Global run queue - when a goroutine is created, they are placed into global run queue

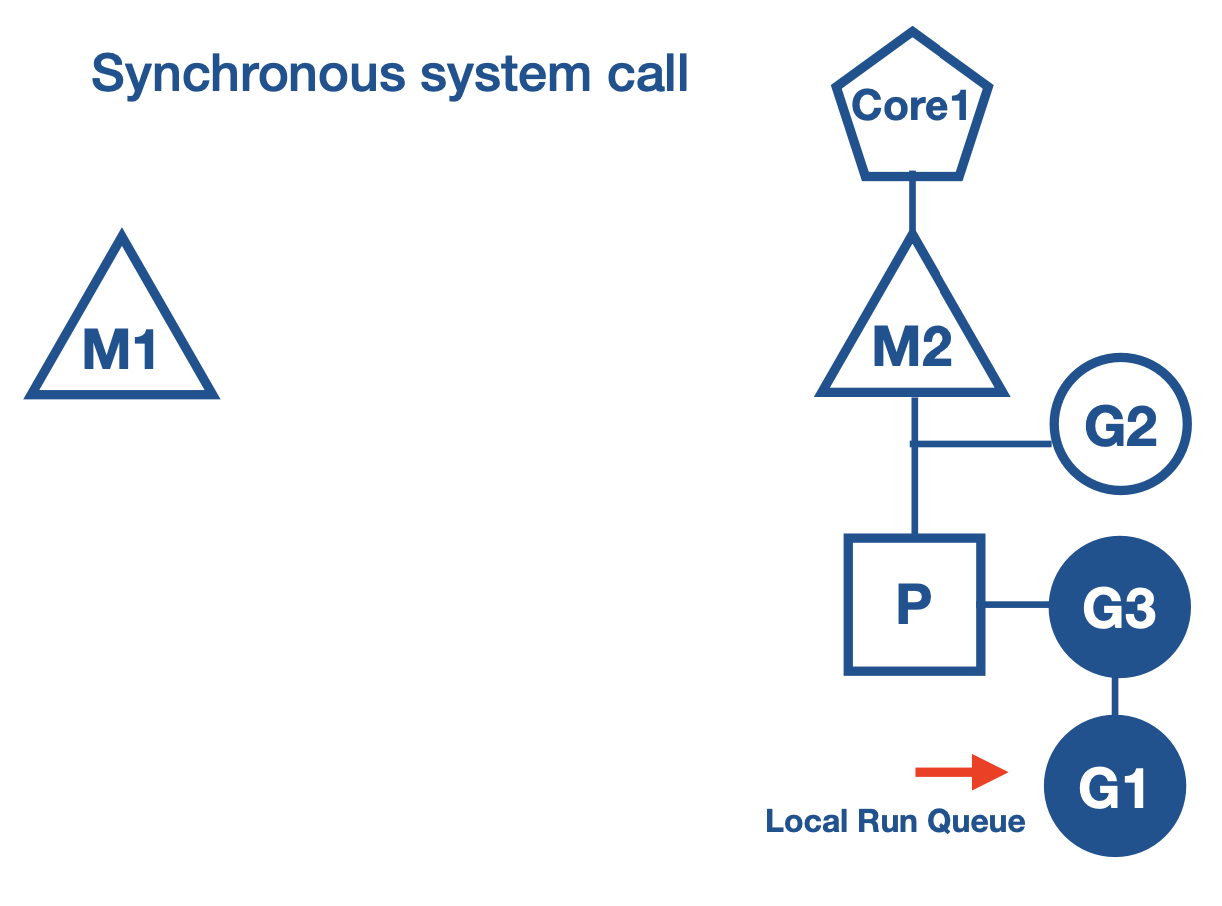

Context switching due to synchronous system call

What happens in general when a synchronous system call is made?

- Synchronous system call wait for the I/O operation to get completed.

- OS thread is moved out of the CPU to waiting queue for I/O to complete.

- Synchronous system calls reduces parallelism

How does context switching works when a go routine calls synchronous system call?

- When Go routine makes a synchronous system call, Go scheduler gets a new OS thread from thread pool.

- Moves logical processor P to the new thread.

- Go routine which made the system is still attached to the old thread.

- Other Go routines in the local run queue are scheduled for execution on the new OS thread.

- Once system call returns, Go routine is moved back to the run queue of P and the old thread is put to sleep

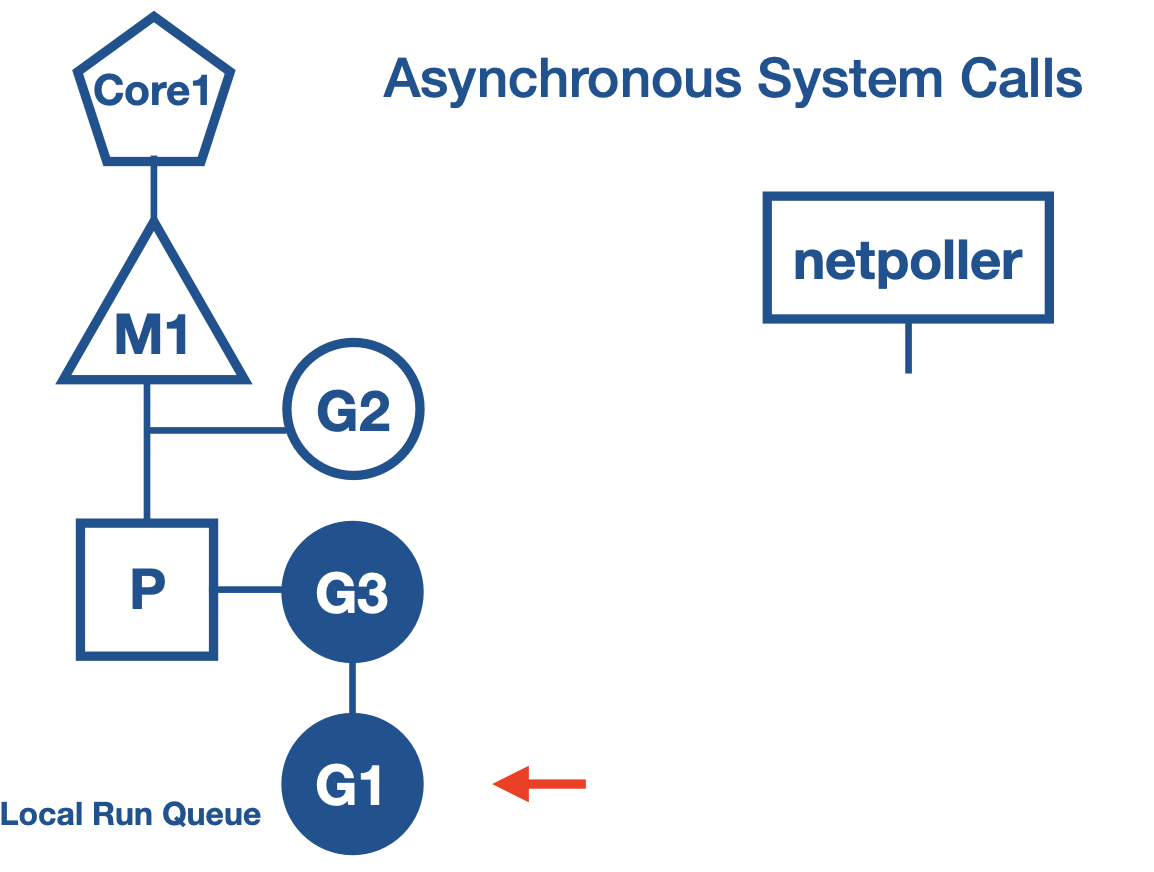

Context switching due to Asynchronous system call

What happens in general when a Asynchronous system call is made?

- File descriptor is set to non blocking mode.

- If file descriptor is not ready for IO operation, it does not block the call but returns an error.

- Asynchronous call increases application complexity.

- Application has to setup event loops using callback functions.

Netpoller

- Go uses netpoller to handle these situations. There is an abstraction built in the

syscallpackage. syscalluses netpoller to convert asynchronous system call to blocking call.- When a goroutine makes and asynchronous system call and file descriptor is not ready, then go routine is parked at netpoller os thread.

- Netpoller uses the interface provided by the OS to poll on the file descriptors.

- Netpoller gets notification from the OS, when file descriptor is ready for operation.

- Netpoller notifies goroutine to retry the IO operation

- Complexity of managing aysnchronous system calls is transferred from application to go runtime, which manages efficiently.

Work stealing

- Work stealing helps to balance the goroutines across all the processors.

- Work gets better distributed and gets done more efficiently.

Work stealing rule:

- If there are no goroutines in the local run queue then

- try to steal from other logical processors

- if not found then check for global run queue

- if global run queue is empty then check for netpoller threads.

Channels

- Communicate data between Goroutines

- Synchronise go routines

- Typed

- Thread safe

- Channels are blocking.

ch <- valueGo routine wait for a receiver to be ready.<- chGoroutine wait for value to be sent- It is the responsibility of the channel to make the goroutine runnable again once it has data.

close(ch)Closing of channel. No more value to be sent.value, ok = <- ch- ok = true, value generated by a write

- ok = false, value generated by a close

Range over channels

for value := range ch {}- Iterate over values received from a channel

- Loop automatically breaks, when a channel is closed.

- range does not return the second boolean value.

Unbuffered channels

- Synchronous

- Sender go routine will be blocked until the receiver go routines is ready to accept and vice versa

ch := make(chan Type)

Buffered Channels

- Channels are given capacity, in-memory FIFO queue.

- Asynchronous.

ch:= make(chan Type, capacity)

Channel Direction

- When using channels as function parameters, you can specify if a channel is meant to only send or receive values

- This specificity increases the type safety of the program.

func pong(in <-chan string, out chan<- string) [].inis receive only channel,outis send only channel.

Default Value

- Default value for channels: nil.

var ch chan interface{}. So we should allocate memory by using themakekeyword - Reading/writing to a nil channel will block forever.

- Closing on a nil channel will panic. Ensure the channels are initialised first.

Ownership - Channels

- Owner of channel is a goroutine that instantiates, writes, and closes a channel.

- Channel utilisers only have a read-only view into the channel.

- Ownership of channels avoids

- Deadlocking by writing to a nil channel

- closing a nil channel - panic

- writing to a closed channel - panic

- closing a channel more than once - panic

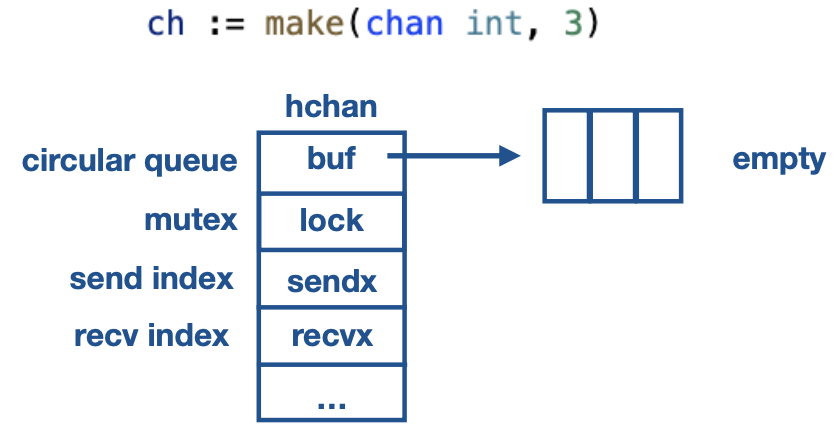

Deep Dive - Channels

- Internally channels are represented by a

hchanstruct.

// Channel structure

type hchan struct {

qcount uint // total data in the queue

dataqsiz uint // size of the circular queue

buf unsafe.Pointer // pointer to an array(circular queue/ring buffer)

elemsize uint16

closed uint32 // if channel is closed

elemtype *_type // element type

sendx uint // send index

recvx uint // receive index

recvq waitq // list of recv waiters

sendq waitq // list of send waiters

lock mutex // mutex for concurrent access to the channel

}

// Linked List of go routines.

// Elements in the linked list are represented by the sudog struct

type waitq struct{

first *sudog

last *sudog

}

// sudog represents a goroutine in a wait list, such as for sending/receiving on a channel.

type sudog struct{

g *g // reference to a go routine

next *sudog

prev *sudog

elem unsafe.Pointer //data element (may point to stack)

...

c *hchan //chanel

}

// elem field is a pointer to memory which contains the value to be sent or to which the received value to be sent.

Channel Initialisation

ch := make(chan int, 3)- hchan struct is allocated in heap.

- make() returns a pointer to it.

- Since

chis a pointer it can be sent between functions for send and receive.

Send and receive in Buffered Channels

ch := make(chan int, 3)

// G1 - goroutine

func G1(ch chan<- int) {

for _, v ;= range []int{1,2,3,4,5} {

ch <- v

}

}

// G2 - goroutine

func G2(ch <-chan int) {

for _, v ;= range ch {

fmt.Println(v)

}

}

Scenario - 1:

G1 executes first

- G1 acquires lock on

hchan - Enqueues the element in circular ring buffer. It is a memory copy.

- Increases the

sendxvalue to 1. - Releases the lock on

hchan

G2 executes second

- G2 acquires lock on

hchan - Dequeues the element in circular ring buffer. It is a memory copy.

- Increases the

recvxvalue to 1. - Releases the lock on

hchan

- There is no memory share between goroutines.

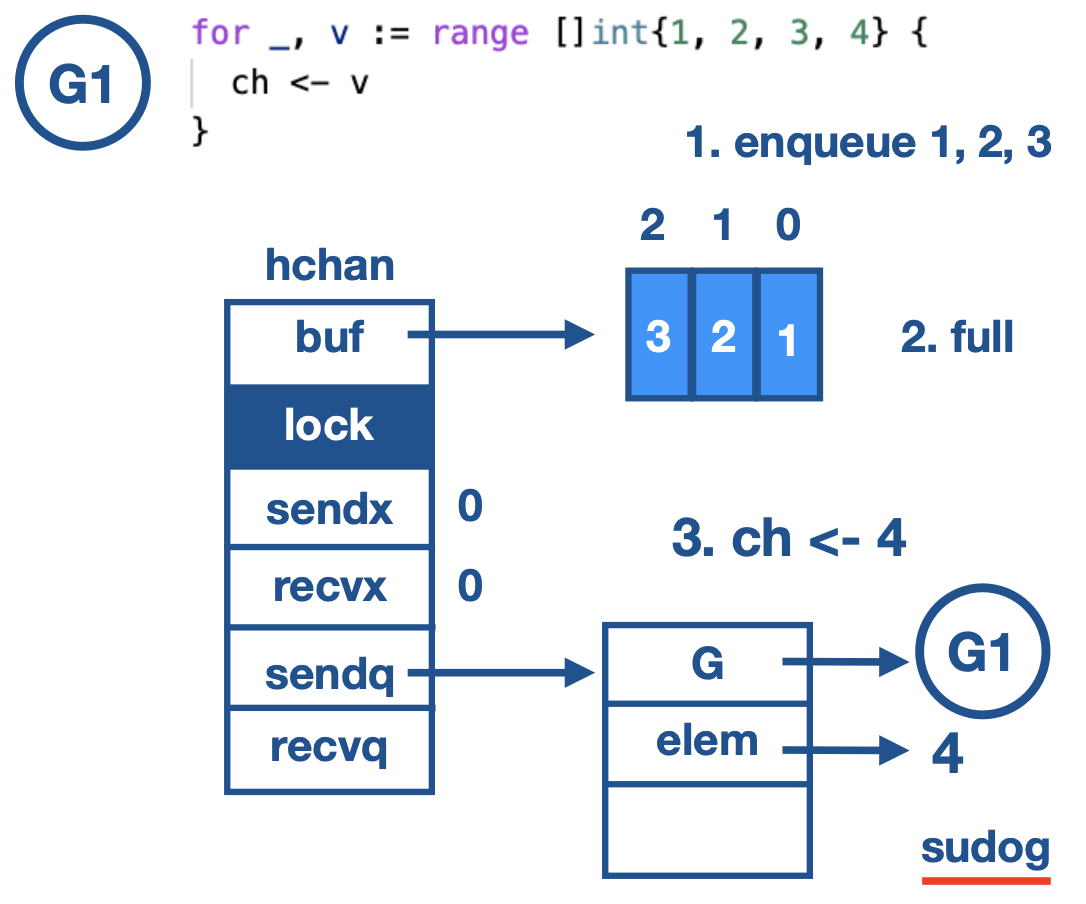

Send when buffer is full

channel buffer is full and a goroutine tries to send value.

- Sender Goroutine gets blocked and its need to wait for the receiver.

G1creates asudogstruct andGelement stores the reference to theG1- And the value to be enqueued is saved in the

elemfield. - This

sudogis enqueued insendqlist. G1callsgopark()and the scheduler movesG1out of the execution and starts executing other goroutines in the local runqueue.

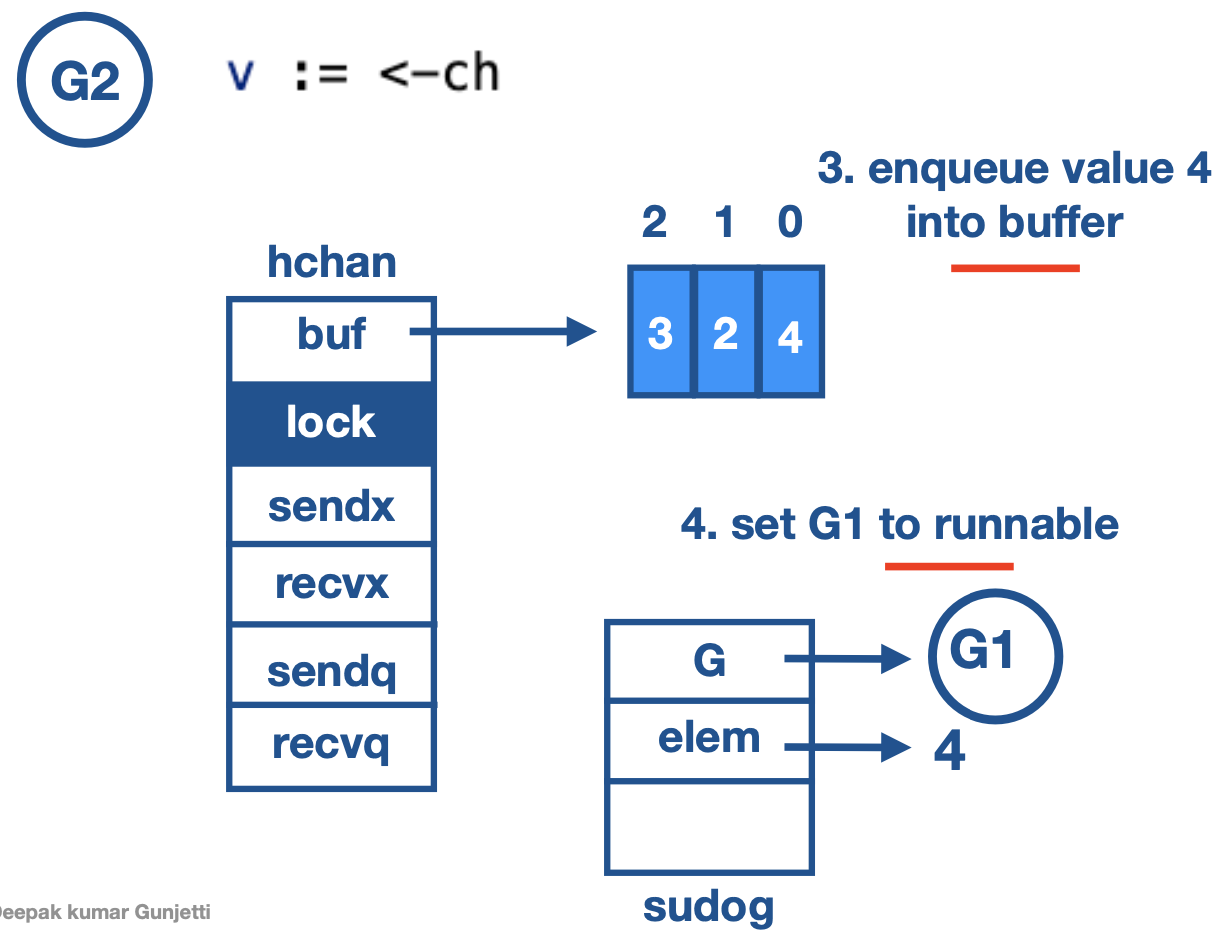

channel buffer is full and a goroutine tries to receive value.

- Dequeues element at 0th index. copies it to the value v

- Pops the waiting

G1on thesendq. - Enqueues the value saved in the elem field.

It is G2’s responsibility to enqueue the value on which G1 was blocked. It is done for optimisation as G1 need not do any channel operation again.

G2SetsG1to runnable. It is done by G2 callinggoready(G1)function on G1

Buffer Empty

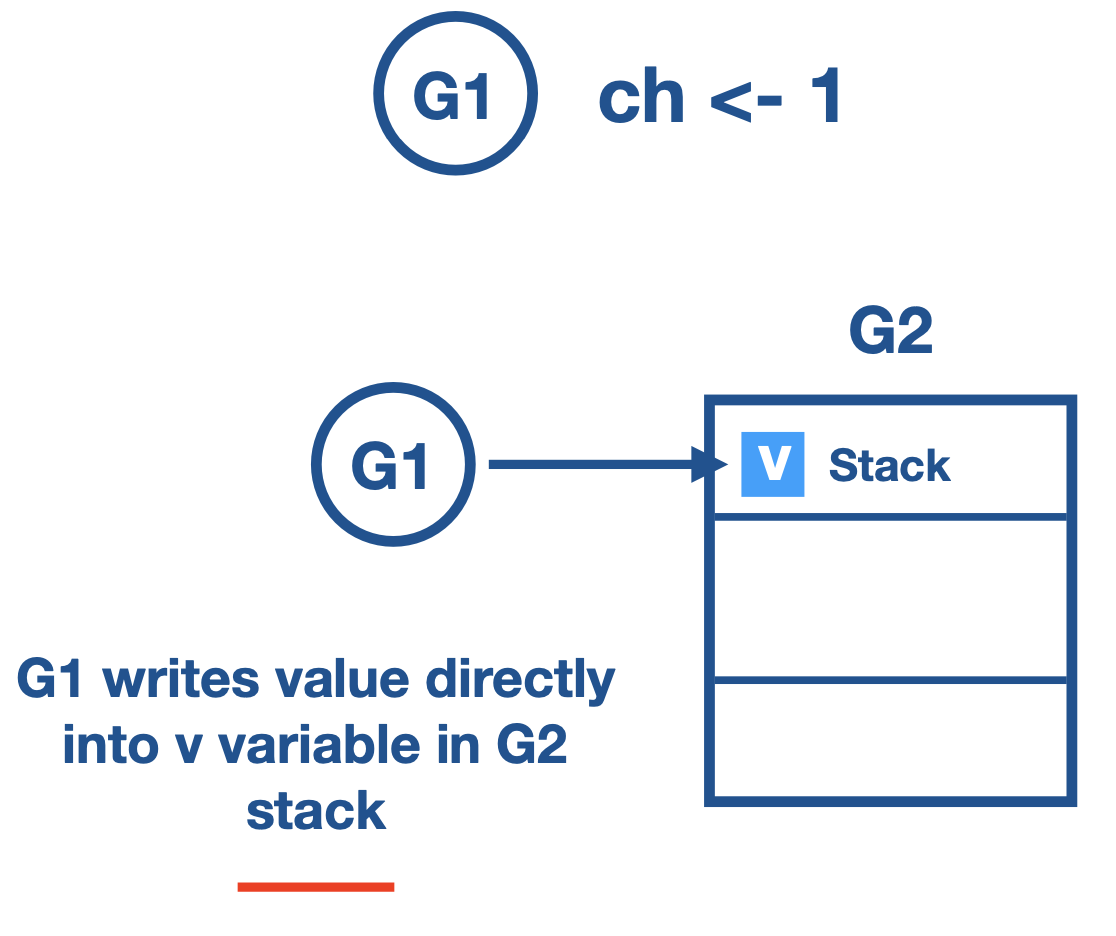

- When goroutine calls receive on empty buffer.

- Goroutine is blocked, it is parked in to

recvq. elemfield of thesudogstructure holds the reference to the stack variable of receiver goroutine.- When sender comes along, Sender finds the goroutine in

recvq. - Sender copies the data, into the stack variable, on the receiver goroutine directly.

- Pops the goroutine in recvq, and puts it in runnable state.

Send on unbuffered channel

- When sender go-routine wants to send values.

If there is corresponding receiver waiting in

recvq. a. Sender will write the value directly into receiver goroutine stack variable. b. Sender go-routine puts the receiver goroutine back to runnable state.If there is no receiver goroutine in

recvqa. Sender gets parked intosendqb. Data is saved in theelemfield insudogstruct c. Receiver comes and copies the data. d. Puts the sender to runnable state again.

Receive on unbuffered channel

- When receiver go-routines wants to receive value

If there is a corresponding sender waiting in

sendqa. Receiver copies the value in theelemfield to its variable. b. Puts the sender goroutine to runnable state.If there was no sender go-routine in

sendqa. Receiver gets parked intorecvqb. Reference to variable is saved inelemfield insudogstruct. c. Sender comes and copies the data directly to receiver stack variable. d. Puts the receiver to runnable state.

Select Statement (Notes to be added)

Sync Package

Mutex (sync.Mutex)

- When to use channels and when to use Mutex?

- Channels are good when we have to pass the copy of data, distributing units of work and communicating asynchronous results.

- In case of Caches, registries and state which are big in size and we want access to these to be concurrent safe. Then we have to use Mutex

- Used to protect shared resources.

sync.Mutex- provide exclusive access to a shared resource.- If a goroutine is just reading a resource not writing, then we can use Read Write Mutex

sync.RWMutex- Allows multiple readers. Writers get exclusive lock.

Atomic (sync.Atomic)

- Low level atomic operations on memory

- LockLess operation.

- Used for atomic operations on counters

atomic.AddUnit64(&ops,1)

value := atomic.LoadUnit64(&ops)

Conditional (sync.Cond)

- Condition variable is one of the synchronization mechanisms.

- A condition variable is basically a container of goroutines that are waiting for a certain condition.

- Conditional variable are of type

var c *sync.Cond. - We use constructor method sync.NewCond() to create a conditional variable, it takes sync.Locker interface as input, which is usually sync.Mutex.

m := sync.Mutex{}

c := sync.NewCond(&m)

c.Signal()

- Signal wakes on goroutine waiting on c, if there is any.

- Signal finds goroutine that has been waiting the longest and notifies that.

- It is allowed but not required for the caller to hold c.L during the call.

c.Broadcast()

- Broadcast wakes all goroutines waiting on c.

- It is allowed but not required for the caller to hold c.L during the call.

Once (sync.Once)

- Run one time initialization functions.

once.Do(funcValue)

- sync.Once ensure that only one call to Do ever calls the function passed in -even on different goroutines.

Pool (sync.Pool)

- It is used to constrain the creation of expensive resources like db connections, network connections.

- create and make available pool of things for use.

b := bufpool.Get().(*bytes.Buffer)

bufPool.Put(b)

Race Detector

- Go provides race detector tool for finding race conditions in Go code

go test -race mypkg

go run -race mysrc.go

go build -race mycmd

go install -race mypkg

- Binary build needs to be race enabled.

- When racy behaviour is detected a warning is printed.

- Race enabled binary will be 10 times slower and consumes 10 times more memory.

- Integration tests and load tests are good candidates to test with binary with race enabled.